A renewed push in the RAP Act bill to shield artists from having their lyrics used against them in court is gaining momentum in Congress.

On Thursday, Representatives Hank Johnson of Georgia and Sydney Kamlager-Dove of California reintroduced the Restoring Artistic Protection (RAP) Act in the U.S. House of Representatives. The bill seeks to restrict prosecutors from using lyrics as criminal evidence unless they can prove the words were meant as literal statements of fact.

The legislation, originally introduced in 2022, failed to advance beyond the committee stage. But with its reintroduction, the RAP Act returns with broader industry backing. Music companies, such as Universal Music Group and Warner Music Group, along with advocacy groups including the Recording Academy and the RIAA, are now throwing their support behind the proposal.

For decades, prosecutors have used lyrics—particularly in rap—to paint artists as criminals. Critics argue the practice unfairly targets Black musicians whose genre often relies on fictionalized narratives and street-based imagery.

“Freddie Mercury didn’t confess to murder. Johnny Cash wasn’t tried for shooting a man in Reno,” said Rep. Johnson, pointing out the double standard often applied to hip-hop.

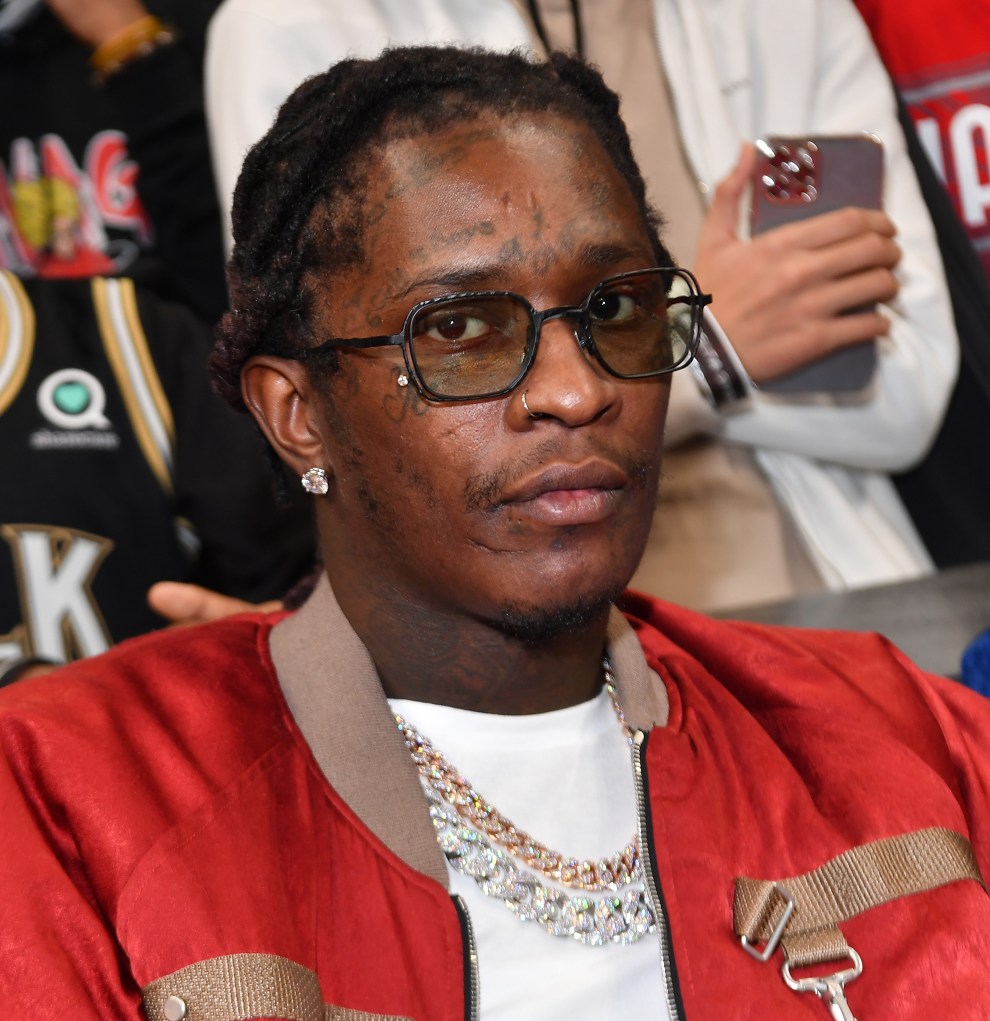

Recent high-profile cases have amplified the urgency behind the bill. In Georgia, rapper Jeffery Williams, better known as Young Thug, faced RICO charges largely supported by his lyrics. Prosecutors claimed his group, YSL, was a gang; defense attorneys argued it was simply a record label. A judge permitted 17 lines of lyrics to be entered into evidence. Williams later accepted a plea deal after spending more than 900 days in custody.

The issue has also bled into civil litigation. Drake’s legal team recently filed a defamation suit against Universal Music Group, claiming Kendrick Lamar’s 2024 diss track “Not Like Us” endangered him and his family. Legal scholars responded by urging the court not to interpret rap lyrics as literal facts, warning that doing so threatens artistic freedom.

Industry leaders are pushing Congress to act. “Weaponizing lyrics undermines expression and chills creativity,” said Recording Academy CEO Harvey Mason Jr. UMG executive Jeffrey Harleston added that lyrics are often exaggerated or symbolic, not confessions of guilt.

As the RAP Act returns to the House floor, its supporters hope this time lawmakers will draw a clear line between poetry and prosecution.

Leave a Reply